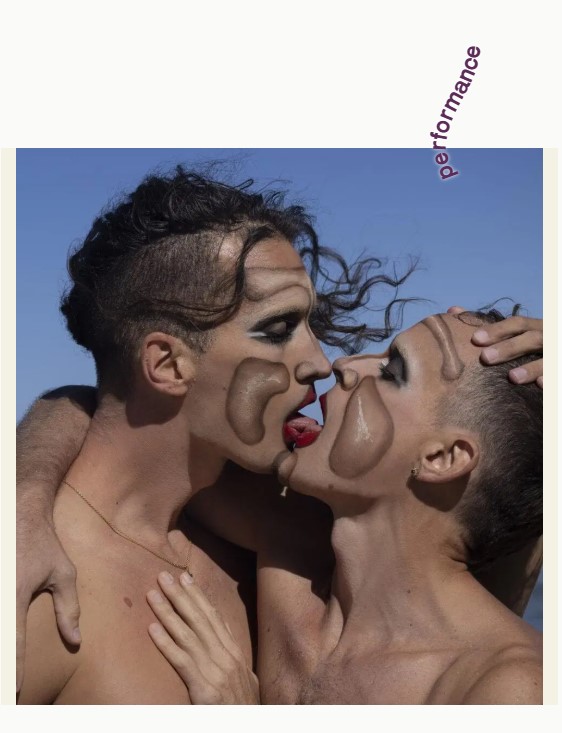

On 12–13 February, Brussels hosts a piece that feels made for queer eyes and hearts: Monica, a deeply intimate performance by Argentinian artist couple Pablo Lilienfeld and Federico Vladimir at La Balsamine. It is part family archive, part telenovela, part quiet revolution against heteronormative ideas of what a mother, a couple, and a family are allowed to be.

A love story with two Monicas at its core

Pablo and Fede have been together since 2014, and from the start their relationship and artistic practice have been intertwined. Their motto, in Spanish, is “Narrarse es cuidarse” – to tell your story is to take care of yourself (and of each other). In Monica, they turn that ethic of care toward the lives of their mothers, both called Monica, both daughters of European war refugees who grew up in 1950s Argentina and later migrated to Spain.

One Monica (Lilienfeld’s mother) died young in 1986, leaving behind a huge body of colourful, hypnotic paintings. The other (Vladimir’s mother) broke with strict Catholicism and posed nude for erotic photographs taken by Fede’s father in the 1980s. These traces – the paintings and photographs – are not just props; they are the visual DNA of the performance. The show becomes a kind of séance in motion, where queer sons dance with the ghosts, desires and contradictions of their mothers.

More information on the venue and dates:

- La Balsamine event page (EN/FR/NL): https://www.visit.brussels/fr/visiteurs/venue-details.La-Balsamine.942

Queer motherhood beyond biology and patriarchy

One of the most powerful ideas in Monica is that Pablo and Fede can consider Monica – the piece, the shared figure of their mothers – as their “common daughter”. The usual direction of family trees is flipped: instead of mothers simply producing children, queer artists “give birth” to a new Monica made of images, performance and memory.

This re-writing of genealogy matters for LGBTQ+ audiences. Many of us grow up with narratives where family is rigid: one mother, one father, one path. Monica offers something else – a non‑heteronormative web of care, where a couple can be co‑parents to a work, to a story, to an imagined lineage that includes the women who shaped them but does not freeze them into traditional roles. The show is described as a “telenovela” in which patriarchal histories, wars and migrations coexist with the stories that were erased. That’s precisely where queer storytelling lives: between what we inherit and what we decide to reinvent.

For broader queer perspectives on chosen family and non‑traditional kinship, you might also appreciate:

- “Queer Kinship: Family Formations and Social Transformation” (book overview and essays): https://www.manchesteropenhive.com/display/9781526114202/9781526114202.xml

- Article on queer chosen families (The Trevor Project): https://www.thetrevorproject.org/resources/article/what-is-chosen-family/

Bodies, archives and the politics of looking

Monica unfolds through performance, dance, video and music, but underneath it all is a question many queer people know intimately: who gets to look at our bodies and our lives, and on whose terms? One mother is present through her paintings; the other, through erotic images that once circulated under the male gaze and patriarchal frameworks. By re‑staging these archives, Pablo and Fede reclaim them through queer eyes – as sons, as lovers, as artists.

For LGBTQ+ spectators, this resonates with the long history of queer bodies being hyper‑sexualised, censored or simply erased. Monica doesn’t offer a simple “celebration” of liberation; instead, it sits with complexity: Catholic guilt and erotic desire, exile and belonging, tenderness and spectacle. It invites us to ask how we tell our stories when the source material comes from systems that didn’t always want us to exist.

If you’re interested in how queer art reclaims the gaze, you can explore:

- “The Queer Art of Failure” by Jack Halberstam (overview and excerpts): https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-queer-art-of-failure

- “Inside the Queer Art of the Archive” (short article on archives and LGBTQ+ memory): https://www.frieze.com/article/queer-archives

Why this matters for LGBTQ+ audiences in 2026

In a moment when queer and trans families are still under attack in many places, Monica feels urgent. It offers:

- A vision of motherhood that is not saintly, silent or straight, but embodied, flawed and desiring.

- A model of queer partnership where intimacy and creativity are inseparable, and where making art together becomes a way of caring for each other’s histories.

- A reminder that our stories do not start with us – they stretch back through migrations, wars, secrets and silences – but we can still choose how they are told now.

If you’re in Brussels or nearby, Monica is not just “something to see”. It’s an invitation to think about your own queer lineage: the women, mentors, lovers, friends and ghosts who made you possible, and the stories you might still want to bring to the stage of your own life.

Practical links to plan your visit:

- La Balsamine official site: https://balsamine.be

- Brussels LGBTQ+ information and events:

- RainbowHouse Brussels: https://rainbowhouse.be

- Visit.Brussels LGBTQI+ page: https://www.visit.brussels/en/visitors/what-to-do/lgbtqi

Even if you go alone, you may walk out feeling a little less alone in your own messy, beautiful queer genealogy.

You may also like

-

Queer Voices, One City: Meet the Choirs of Various Voices Brussels 2026

This June, Brussels turns into a queer soundscape: 120 LGBTQI+ choirs from 18 countries are

-

Lou Queernaval in Nice: When Queer Celebration Takes Center Stage

On February 27, Place Masséna in Nice became a queer epicenter. For its 11th edition,

-

Niall Horan, Soft-Spoken Pop Star – And Loud LGBTQ+ Ally

From Pride tweets to rainbow flags in the crowd, Irish singer Niall Horan has quietly

-

Angèle x Justice’s “What You Want”: A Queer Night Out We’ve All Dreamed Of

Projected onto the façade of La Monnaie in Brussels and shot at night in Marseille

-

Ten Years of Balkan LGBTQIA: A Decade of Fighting Borders, Discrimination and Silence

Created in Brussels by volunteers from across the Balkans, Balkan LGBTQIA has spent ten years