In April 2012, a young man from Liege, Ihsane Jarfi disappeared after being seen one last time leaving the Open Bar, a gay bar in downtown Liege. His naked body is found two weeks later. He had been beaten to death by four men. The crime was judged by court as the first homophobic murder in Belgium and changed the course of history concerning LGBTQIA+ violence. Hassan Jarfi, Ihsane’s father dedicated his life to spreading the word since the events. He has founded the Ihsane Jarfi Foundation and Refuge.

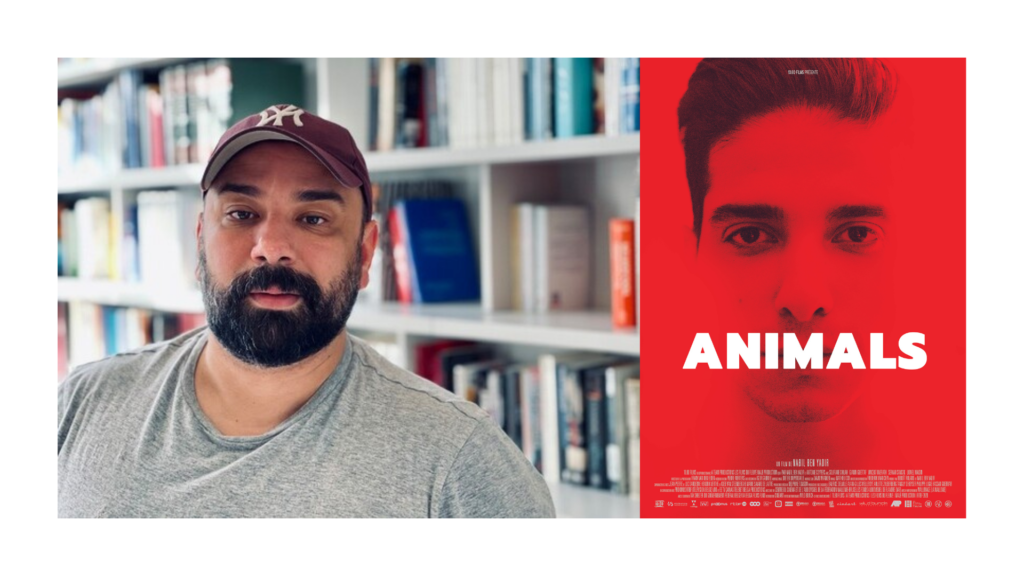

“Animals” is the story of Brahim (played by Soufiane Chilah). His story is inspired by the life and death of Ihsane. Nabil Ben Yadir acted as a true LGBTQIA+ ally by telling this story in his movie. He wants youngsters to be able to see this movie and discuss minority and discrimination issues in classes through the spectrum of violence.

After being presented in several festivals such as Pink Screens Festival and Ramdam Festival, the movie is now on general release.

We met with Nabil Ben Yadir to know more about the movie :

This film is an important and anticipated film for the LGBTQIA+ community given the subject matter. How did you come up with the idea of tackling this theme of homophobia?

Above all, it is the story of Ihsane Jarfi that really brought me to this, what he lived through, what he had to undergo during that night? His personal story brought me back to this theme by force of circumstance. And then I followed the trial and I asked myself: how can it still come to this now? The crime is considered by the Belgian justice as the first homophobic murder, that is to say, murder with the aggravating circumstance of wanting to kill because of hatred linked to the sexual orientation of the victim. I was quite upset by what he had experienced. So I wanted to appropriate this story by making it fictional, but by being close to reality. It’s complicated to develop a film like that, raw, violent. It is not easy to make, to finance, and to be able to make this film exist. The idea came to me one day when I was reading a newspaper. The first article on the case said that the body had been found and that it was a homophobic crime. Already at that moment, I asked myself why it was only a homophobic crime and not also a racist one. How are we defined? Does sexuality take precedence over origin? I was in a café with some buddies and one of my buddies had a pretty horrible reaction and said: He’s a faggot, let him die. He said this with a rather disconcerting lightness. I didn’t react at the time, and then I felt bad for not reacting. I came back the next day to the same café with the same newspaper. He said: Ah, you’re still in this article? I told him yes, and that I was going to make a movie about it, even though I didn’t have the exact idea yet. It was important to be able to talk about it afterward with this person because he saw the film before anyone else. It was quite interesting because there was a difference between the person who said that sentence and the person who saw the film afterward. I don’t think you can get out of the movie unscathed, it’s impossible. It’s the difference between a few lines of news and an hour and a half long movie.

The film aims to change mentalities and that’s why you decided to show the violence as it is. Can you explain it to us?

The question of the representation of violence was always in the making, from my first encounter with the subject to the editing. For me, it had to be represented as it was. It had to be raw and as realistic as possible. I think that the cinema which suggests is a cinema that exists and which has its place as much as the raw cinema. The idea is not that you walk out of the film and forget about it, move on and go to a restaurant or bowling. You are not really in the mood to eat after seeing the movie and that’s obviously on purpose. I remember that we did a screening at the Pink Screens Festival. It was a very moving debate, very strong, very powerful. And then one person said that it brought him back to personal stories. The film was unbearable for him. But I answered him: can you imagine if I had made a bearable film? The question is there. There is popcorn cinema and then there is this kind of cinema. When you go to see this movie, you know what you get yourself into There is a reflection behind it, so we know why we are making the film, we know that it will disturb, that it will shock, but I could not imagine doing it otherwise.

To prepare the writing of the film, you attended the trial of the Ihsane Jarfi case. Can you tell us how you lived this experience?

It was very strange. It was the first trial that I followed. It is precisely there that I did not have the impression that there was an awareness on the part of the murderers of the lightness with which they committed this act. The fact that they could have saved him every time, but they let him die. They could have had a renewed sense of humanity and gone after him, but they didn’t. That obviously disturbed me. And it is in the elements present in the third part of the film, which we will not reveal, that I became aware that there was perhaps a story to tell cinematographically. I think that the shortest and most efficient way to the real is through fiction. I think that once in a lifetime you might run into someone who has never read an entire book, but you will rarely run into someone who has never seen an entire movie. I think this tool is very important. And then this trial made me realize that there is a factory of monsters and that these monsters can sometimes have the faces of angels.

The film has already been previewed at the last edition of the Pink Screens Festival. How do you think the film will be perceived by the LGBTQIA+ community itself?

That’s not my target audience. I said so before I started the film. My goal is to reach unconvinced people. The LGBTQIA+ community already agrees that this is a horrible act. We agree that it shouldn’t happen again. We agree that this is a societal political debate and that we must try to put it on our governments agendas. This is the only way to do it. I am not interested in having a debate with people who already agree with each other. The idea is to be able to reach people who might be attracted by violence or who might have found themselves in the car and not in Brahim’s place but in the place of the others. That’s what interests me. That’s why there is an educational project linked to the movie. I think that it’s a film for young people, and it’s quite strange. And the idea is that we don’t prevent young people from going to see the film.

Is it correct to say that you wanted to emphasize the intersectionality of Brahim’s character? Is this the key to bringing minorities together to alleviate discrimination?

I think that the character of Brahim who represents Ihsane died because he was at some point different from the others. He found himself in a place where he represented a minority. It could have been a woman in that car with four guys or a black man surrounded by four cops in a van. I think that’s what interests me, is to say that we can all find ourselves in that situation. He was killed because he was different. I am of Muslim faith and of Arab origin, I am already part of a minority. Ihsane has two “defects” in the eyes of oppressors. One cannot be against one kind of discrimination and close the eyes towards another, it is not possible. The objective is to make everybody understand that. And unfortunately, that’s what often happens and that’s what’s horrible. Sometimes you’re going to have people from the LGBT community who are going to be racist towards other people, and that’s also something that needs to be fought. So the idea is to say, we can all find ourselves in this situation. The character of Brahim is homosexual and that’s why he died. But we can find ourselves in another place where we represent another minority and we risk our lives too. How can we create this crazy relationship with others that are different ? How can we become so resentful towards people who are not living like ourselves ? It’s mostly a question linked to the concept of minority. We are all different from each other in one way or another and we are all at some point intrinsically part of a minority at some point in our lives.

A real educational project for schools has been set up by the film team and is proposed to follow the viewing with young people. the idea is to be able to debate several notions such as minority, discrimination and intersectionality in classes. Can you tell us more?

It was really important for me that this movie was supported by an educational project because it can be interpreted in one way or another. The idea is that the teachers can use this movie as a learning tool. The educational project was made by specialists. We didn’t do it ourselves. Even I learned things about the movie by reading it afterward. I found it very interesting to have someone with some distance to tell the story. It’s a daily struggle. You know, some people will find the film very violent. I’m not saying that young people don’t find it violent enough, it’s not that at all, but they are less shocked by the violence, they are rather shocked by what happens to Brahim’s character. The violence as it is represented, thanks to the educational project, will be followed, structured, debated and it is interesting. This is why the film’s target audience is young people. It would be horrible to see older ones deciding that this movie is not made for young people. That’s what happens all over the world, we decide in the place of others. And that’s why we surrounded ourselves with professionals to build this educational project. They are people who are used to this, who regularly work with schools. They followed us and analyzed the movie in a social, sociological, and educational way.

Can you tell us about your meeting with the Jarfi family and the members of the Ihsane Jarfi Foundation?

I am mainly in contact with Hassan Jarfi, who is kind of the spokesman for the family. Afterward, I also met Nancy, the mother, but it is especially the father who is the driving force of the whole family concerning this fight. It is his battle horse. He is of course part of the Ihsane Jarfi Foundation. My contact was mainly Hassan. He is the person who is at the center of all this commitment. If he had refused to let me make the movie, I wouldn’t have done it. It’s obvious, beyond the freedom of power, it would have been impossible for me to do it against their will. Hassan also supports the movie without seeing it. He was present at the premiere to support it and to talk about his son, which is the most important thing for him.

You may also like

-

Kongi: Ancestry in Motion

Born in Kinshasa in a lively multigenerational home, they migrated first to Paris, then to

-

BREAKING FREE: Trans Icon Johan Jenny Ehrenberg Comes to Brussels

When a voice like Johan Jenny Ehrenberg’s reaches Brussels, it’s more than an event —

-

Ricky Corazon: Creating Latin Queer Space in Brussels

DJ and event producer Rodrigo Aranda, aka Ricky Corazón, takes us into his journey of

-

Ralf Schumacher’s Gay Wedding & the New F1 Season: Why It Matters for Queer Fans

Former Formula 1 driver Ralf Schumacher is getting married to his partner, French politician Étienne

-

Antoine Delie: Turning Hate Into Harmony

There’s a moment, somewhere between the cracked voice and the held note, when Antoine Delie