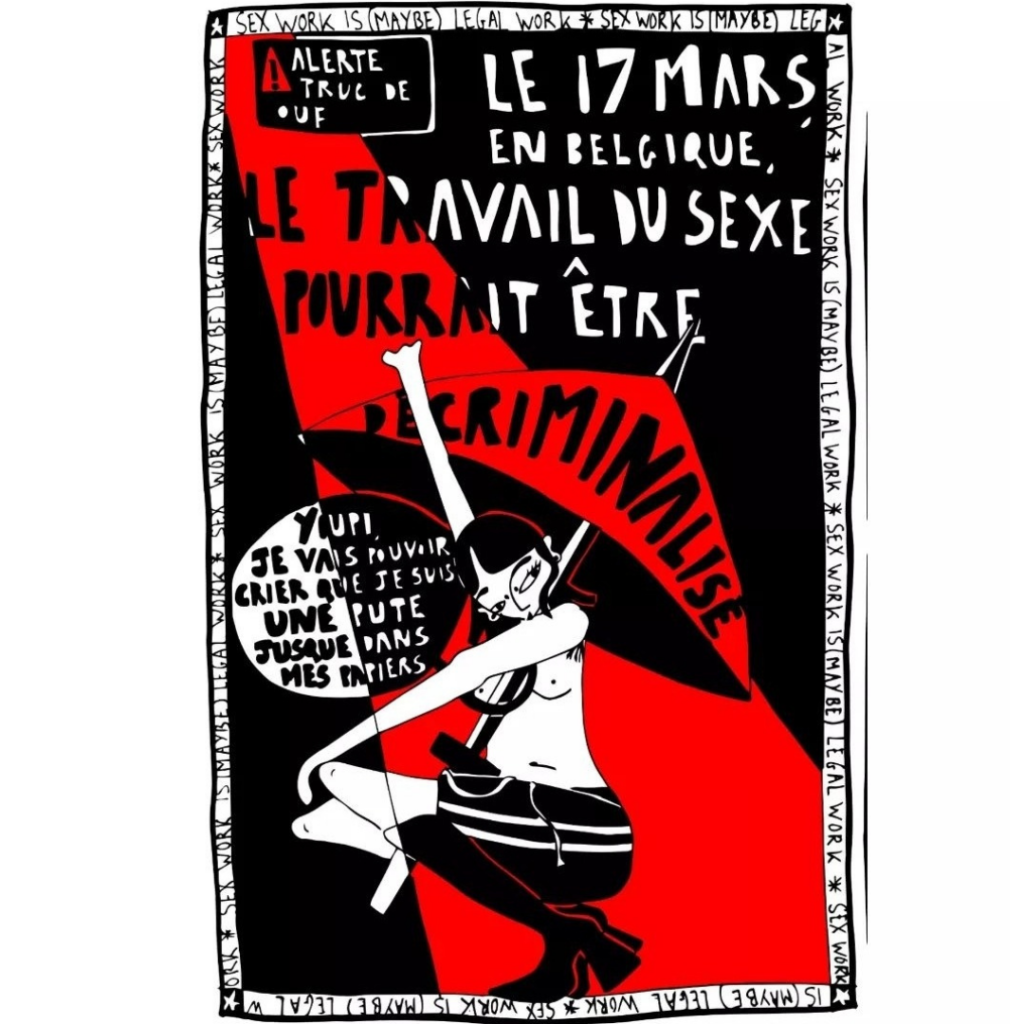

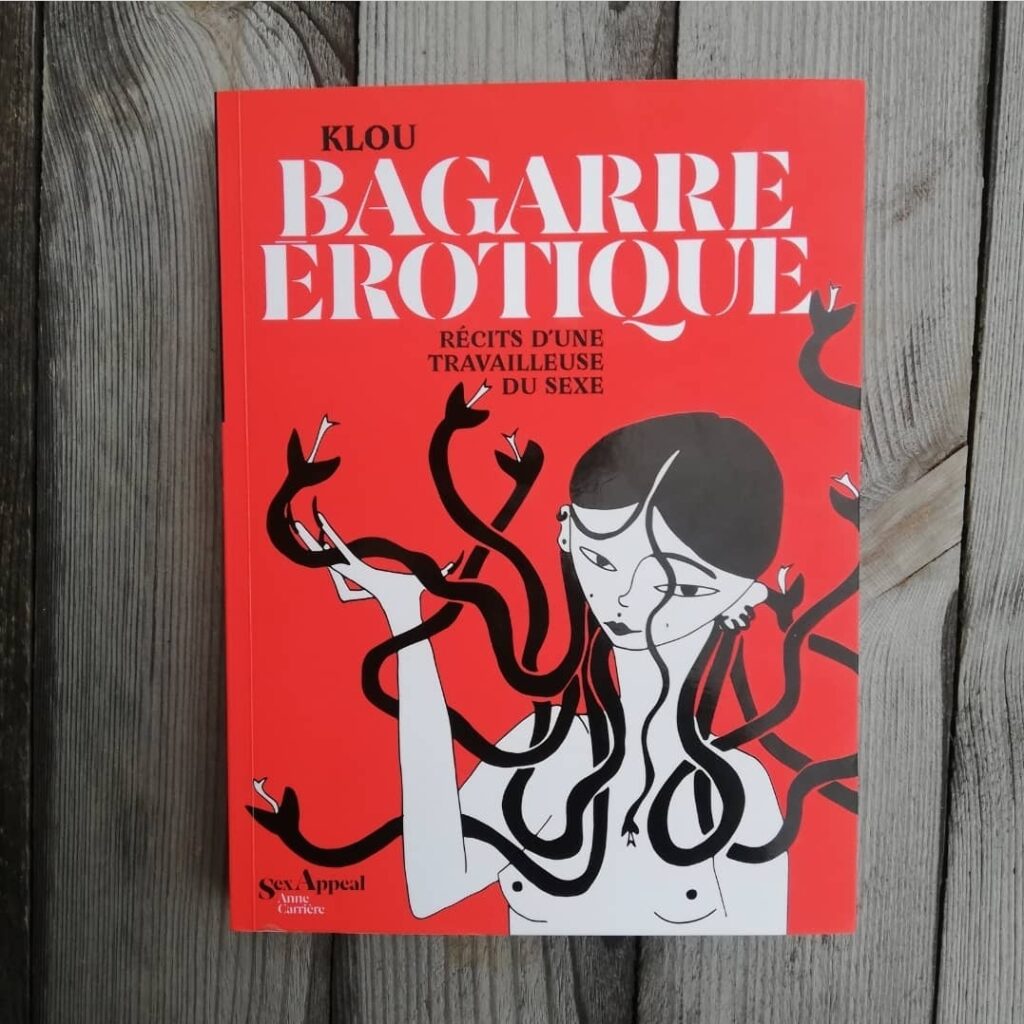

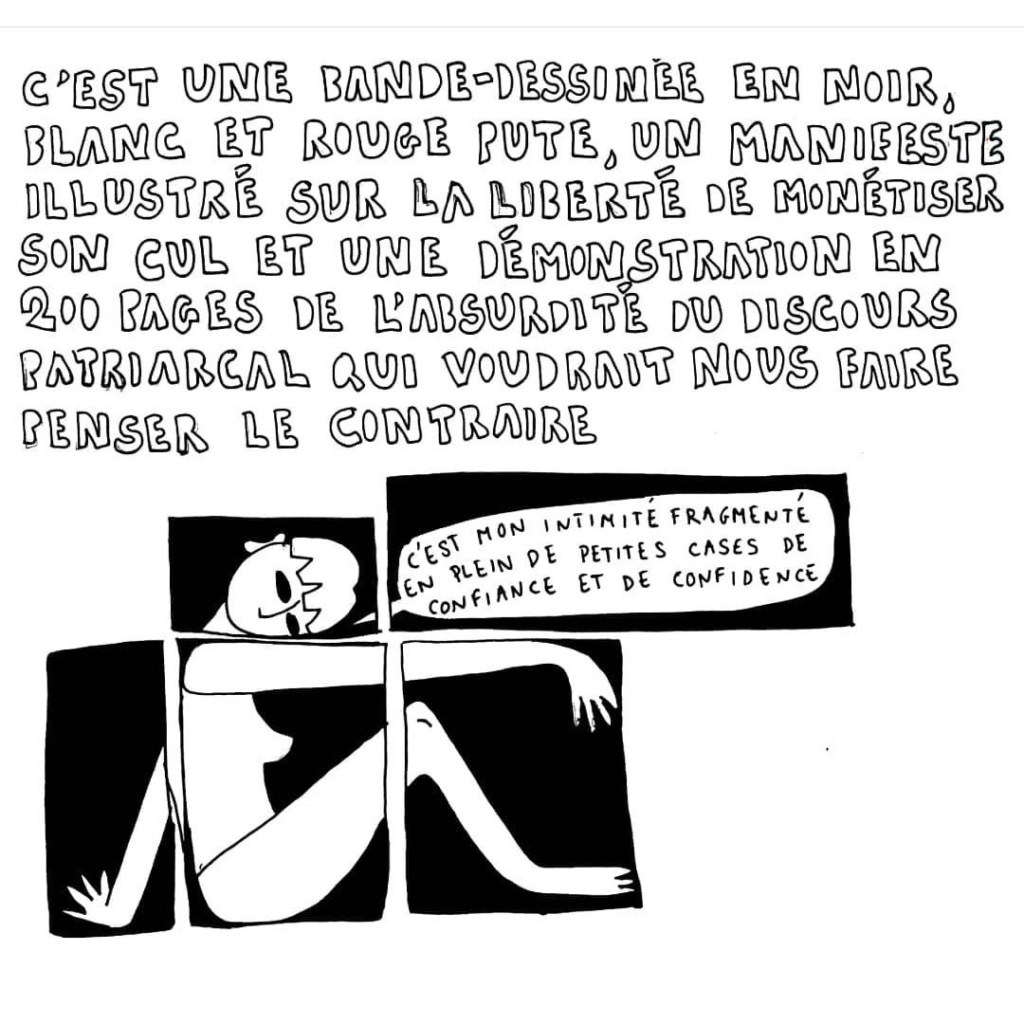

On 18 March 2022, Belgium became the first country in Europe and the second country in the world to decriminalise sex work. A victory for SW activists. And one more reason to get informed about the importance of this reform. Therefore, we strongly advise you to run to your nearest bookstore to buy Klou‘s (she/they) new comic book “Bagarre Erotique – Récits d’une travailleuse du sexe” published by Editions Anne Carrière, a cathartic, educational, feminist and 100% queer work that recounts her experience as a sex worker.

The following interview was conducted a few weeks before the passage of this reform.

In this book, you explain that you felt the need to tell your story because you didn’t hear many voices like yours. Why do you think sex work (SW) remains a taboo today?

I think one of the biggest problems with SW is that there are a lot of people who are not in favour of it because they are not aware that there are sex workers doing this job out of choice and in a consenting way.

A part of the population is abolitionist in a political way, they think that we are so matrixed by the patriarchy that we are OK to “be raped”. This is, in short, their vision. They know we exist but they don’t want to hear us. However, there is also a huge part of the population that is simply educated by and within this hyper-abolitionist society and is, therefore, not aware that we exist.

I think that the first way to educate people is just to make ourselves visible and to show that there are willing and proud sex workers. The real problem is that the society doesn’t want to hear us or see us. Most of the time, we don’t even have space in feminist events.

We have been so demonised in the collective imagination that we are actually considered as monsters. We have to break these stereotypes and show that we are just like any other human being.

We also tend to be hyper-fantasised as sex workers. There are often two perceptions of us – either the victim side as “people to be saved”, or the idea of the hyper-sexual character, a vamp. Explaining that we are neither one nor the other but just ‘random’ people who are a bit tired of capitalism and for whom this job allows for lots of free time, I think this is how we can break the cliché.

You give the definition of pro-sex feminism and explain that the movement started in the United States within the LGBTQIA+ community. What do you think is the connection between queer and SW struggles?

I think both struggles really go hand in hand. We’re populations that are discriminated against because of our sexualities, so necessarily, we understand each other in our oppressions.

And then there is the whole questioning of heterosexuality as a political system. This is a point on which sex workers and queer people meet each other. Heterosexuality can be something that we use or that we reject, and that is super political.

On the one hand, there are queer people who reject heterosexuality because they have grasped its oppressive character. And on the other hand, there are the sex workers who monetise and use heterosexuality and so, in a way, will no longer be subjected to it, in a similar manner as queer people.

You write “Even if the patriarchy disappears one day, sex work will remain, I will simply have as many female clients as female colleagues. And I must admit I’m a little tired of heterosexuality. So I’m kind of looking forward for sex work to be organized by and for queers”. Can you elaborate on this?

Actually, for many people it seems like sex work is hyper patriarchal but it could be totally different if women would just go to sex workers too. It would be a great way to ‘de-patriarchalise’ sex work.

By the way, there is a brothel in Holland exclusively for dykes. And that’s kind of what I would dream of creating in Belgium. A self-managed brothel, without bosses, just between sex workers, the relationships would be without hierarchy, a bit like a cooperative but it would be exclusively queer. For that to happen, we would just have to reach decriminalisation. And that is the number one struggle of sex workers. It would allow us to create spaces without hierarchy and to help each other.

One of the reasons why sex work is not yet queer is also because the queer community remains a minority population, with little purchasing power. I don’t know many queer people who have €200 to pay for an hour of sex.

On top of that, we, as women and gender minorities, have a bit of a shame regarding this topic. Several people around me already told me that they have thought about it, but it usually stops there. To act on it, it seems dizzying to them. But it’s by educating people, by showing that it exists, that it’s OK and that we’re super into having queer clients that we’ll be able to slowly de-patriarchalise sex work.

You emphasise the importance of decriminalising sex work. Could you summarise in a few words the current situation in Belgium and your demands?

In Belgium, sex work in itself is legal. In fact, you just can’t declare it because there is no official status. So you can’t get caught because you’re doing sex work, but as you don’t have any real status, you can’t have access to a normal worker’s rights. And so it’s hyper hypocritical as a law, because to do something legal, you have to go through illegality, that is to say that you don’t have the right to solicit on the street or advertise on the Internet.

So, what we are asking for is simply the suppression of these criminalising laws and a legal status – in order to be able to work in a totally legal way, to be considered as any other workers, to have access to social security, and also to break this stigmatisation around SW, among others.

You explain that SW activism must go hand in hand with the struggle for the regularisation of undocumented migrants. Can you tell us more about the link between the two?

I think there’s a very important connection there. If we decriminalise sex work, there will be, on one side, the workers who will be able to work in a safe and framed environment, but on the other side, there will be undocumented people who still won’t have access to social security for instance, and this could lead to a very unequal situation. Personally, I’m not in favour of this at all. Because it would mean that I would get great conditions at the expense of other people.

But on the other hand, the recognition of SW as an official job could allow undocumented sex workers to prove that they are actually working and therefore to start the process of obtaining a residence permit more easily.

Would you like to tell us about the concrete SW struggle on the ground, do you have any examples of recent actions for example?

At the moment, we have several colleagues who are being evicted from their windows mainly in the area of the North Station/Isère. In fact, the municipality really wants to gentrify the area. And we, sex workers, are still really considered as dirty beings degrading the neighbourhoods. It’s horrible because they find any excuse to get rid of sex workers in these areas.

Recently, a friend of mine was evicted and we were able to create a support on the spot the same day. We knew about it because she was able to tell us about it. But there are also plenty of undocumented sex workers who have no connection with these support networks and who are therefore very easy to evict. And so it’s really important to fight hand in hand, so that people with documents – who face less risks – can be on the front line in this kind of situation, in support of undocumented sex workers.

How did your job influence your activism in general?

Before starting sex work, I was already a feminist but it was a different kind of feminism. It was mainly through the SW community that I learned a lot. In fact, for the first couple of years I was pretty isolated, I didn’t know any other sex workers. And then, at a certain point, I got fed up with the job and it was mainly due to the isolation. I really needed to talk to people who deeply understood me. When I met other SW it really helped me and I started to be more politically engaged, because they reassured me that it was normal to be angry. By meeting and discussing with them, I was able to transform this anger into a political strength.

Since I belong to several communities, there were a lot of things that interconnected: queerness, sex work and being a precarious person. I discovered that I felt super close to other people who experience similar oppressions. For instance, in feminism, there is a lot of solidarity between women and gender minorities, but sometimes I also feel very close to a cis-gay sex worker guy because we experience two oppressions in a similar way: SW and queerness.

To learn more about Klou’s work, you can follow both her Instagram accounts: @klou_bagarre and @kloutattoo

Picture credits : Anouk Durocher

You may also like

-

Interview with JJ, Eurovision 2025 Winner: “Live Each Day with Pride, Because We Are Unstoppable”

With his “pop opera”—as he defines his music—JJ brought victory to Austria at the recent

-

Midsummer Mozartiade: Celebrating Mozart and the Labyrinth of Love in Brussels

From June 17 to 22, the Midsummer Mozartiade festival returns to the heart of Brussels

-

Edy’s VERTIGO : Finding Truth Between Borders and Beats

” I was afraid to surrender,” says Edy Dinca, the Brussels-based queer artist behind the

-

Valenciaga – Born form love, dressed in power

Brussels is well acquainted with queer creativity, but sometimes a voice emerges that leaves a

-

DAY-8-“Safety, Dignity, Belonging” Andrea’s mission at Wowen Now

In Brussels, Andrea from Women Now is on the front lines supporting LGBTQIA+ migrants and