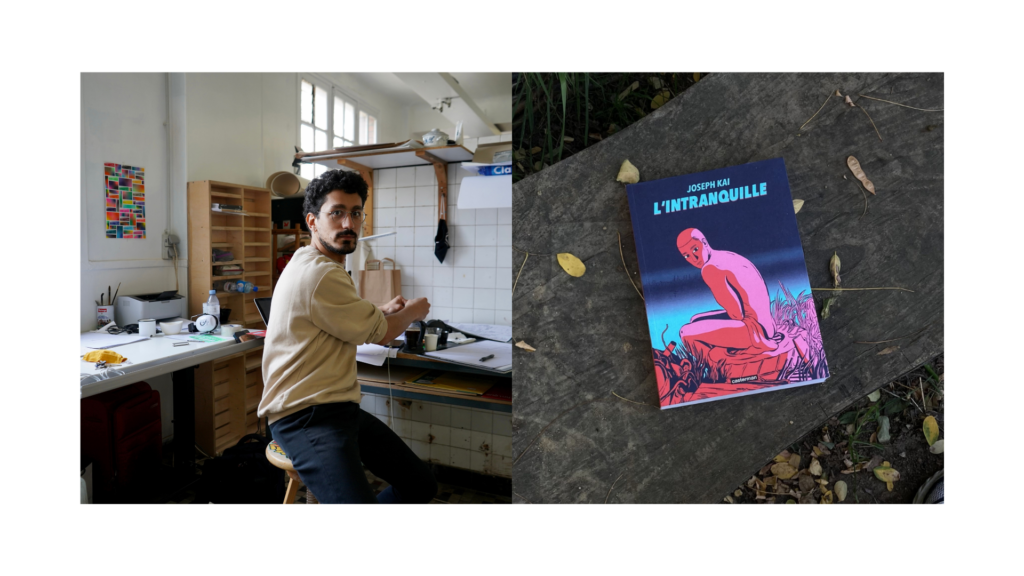

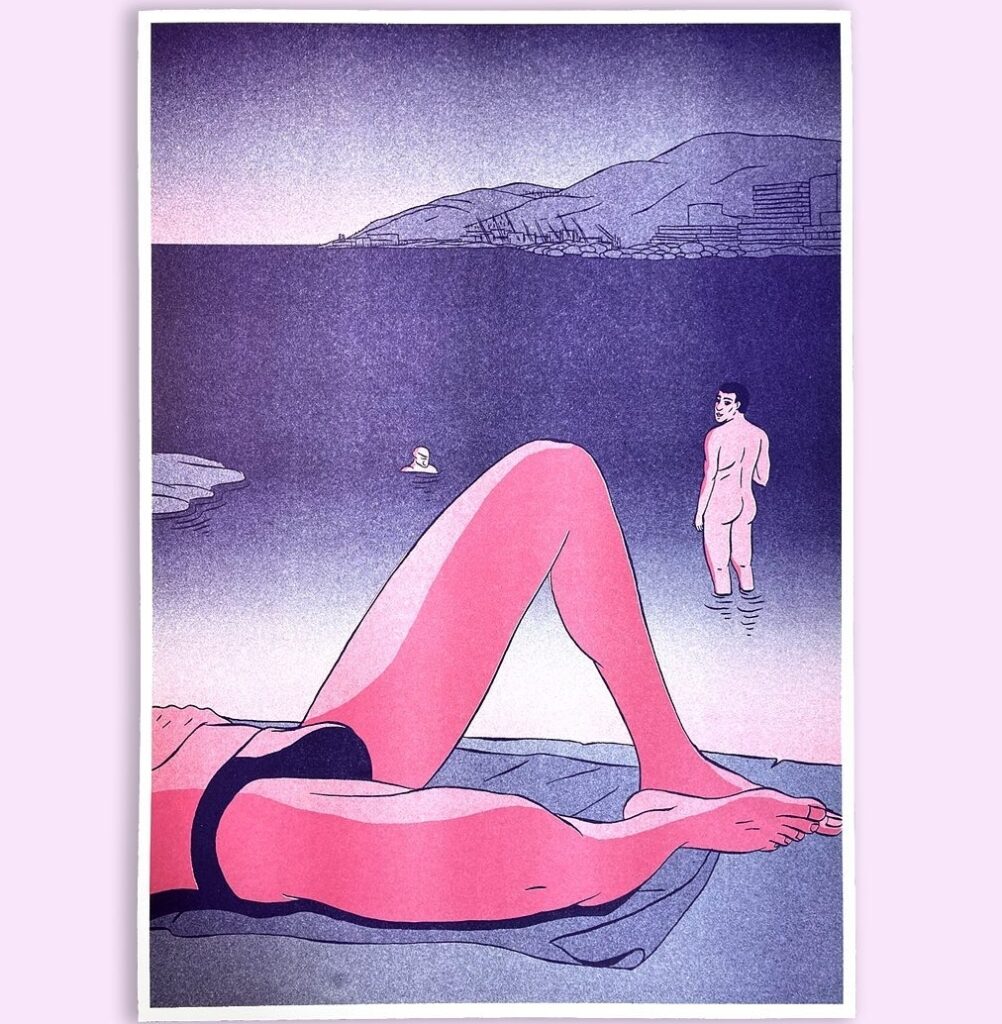

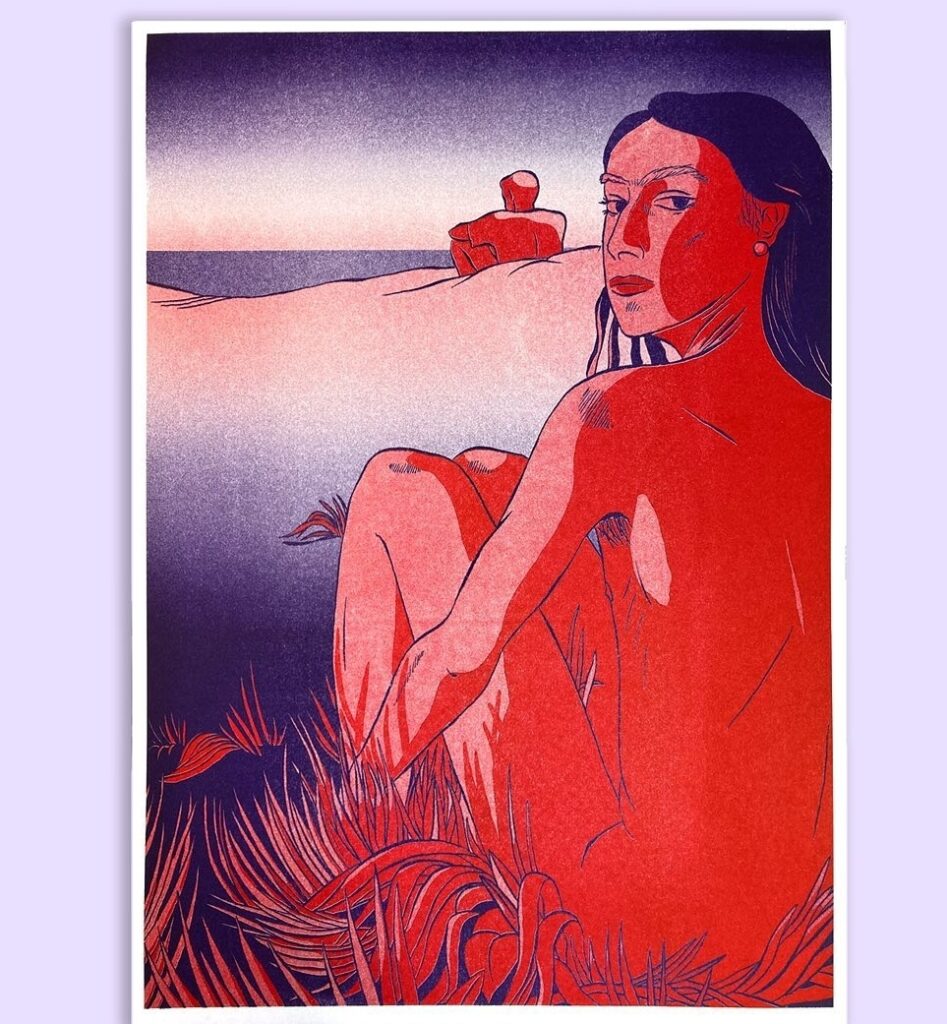

Joseph Kai first graphic novel “L’intranquille” published by Casterman follows the everyday life of Samar. He is a cartoonist, is 30 years old, and lives in Beirut. In the capital, he marches almost every day against corruption while trying to live his homosexuality as well as possible in a country where LGBTQIA + people are repressed, but where there are sometimes, still, spaces of freedom that are often threatened.

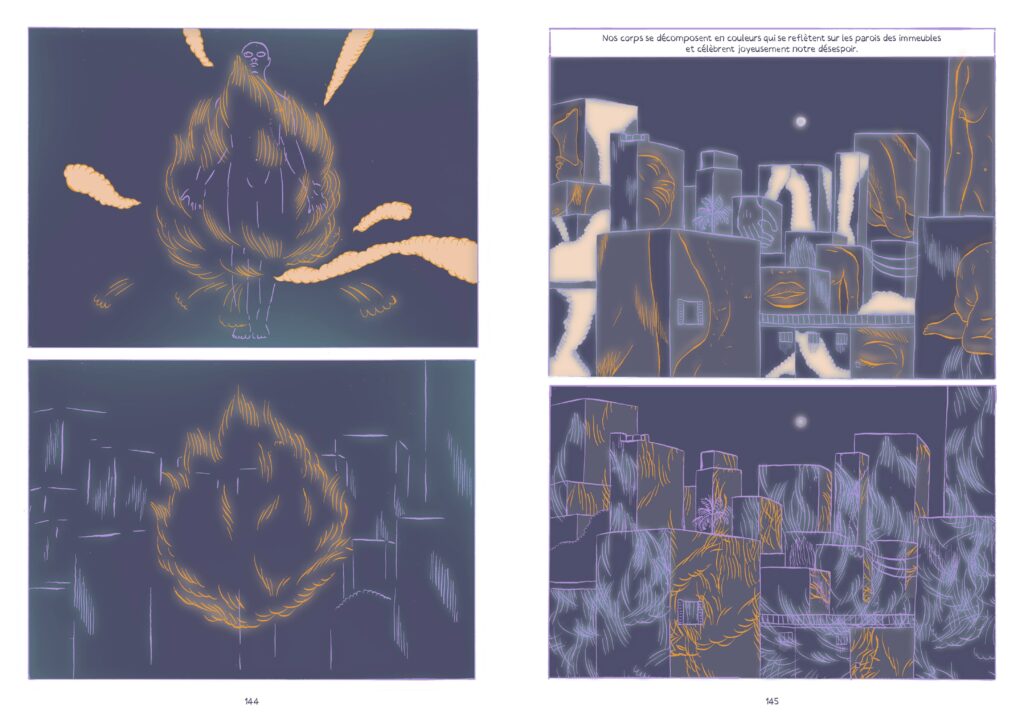

As a spokesperson for the Lebanese queer movement, the author explores, through his hero Samar, the fears and doubts of a youth bruised by homophobia, unemployment, and war, which he exorcises in a work strong in poetry.

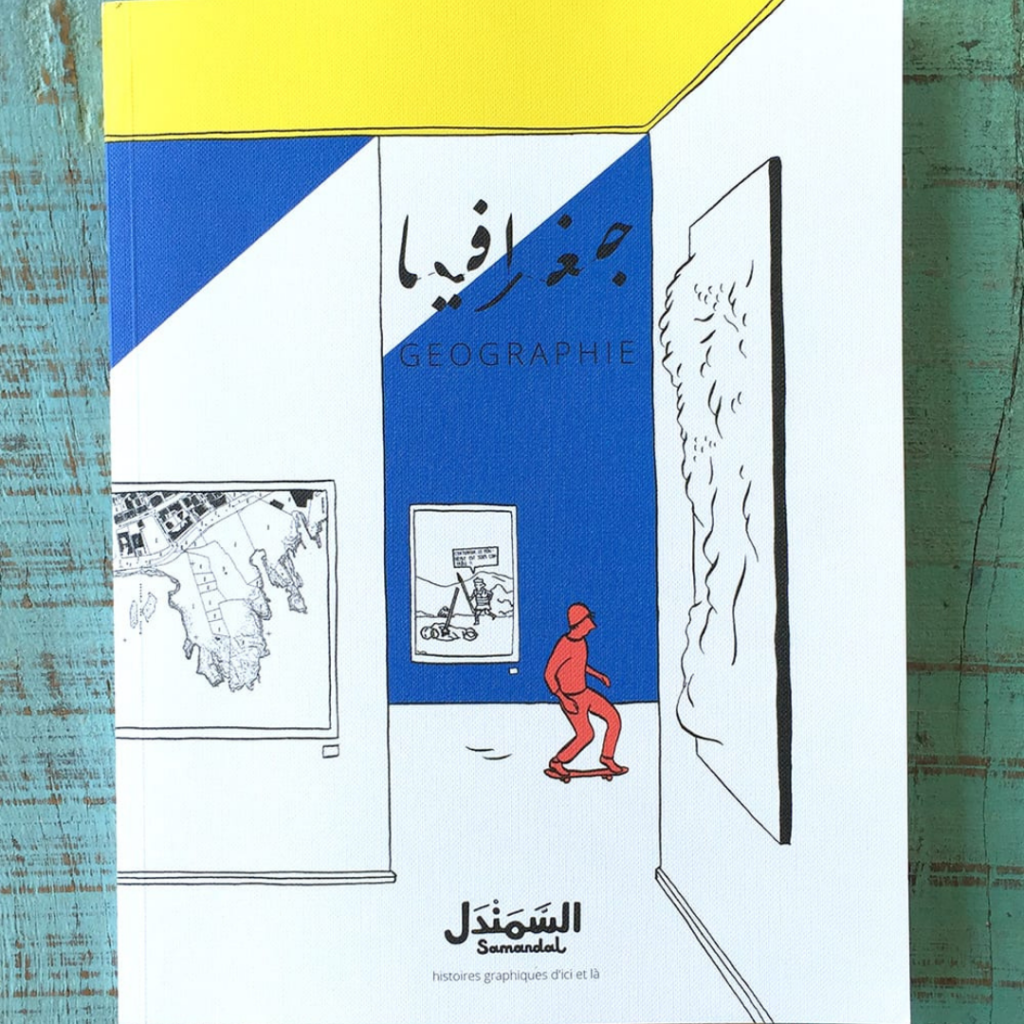

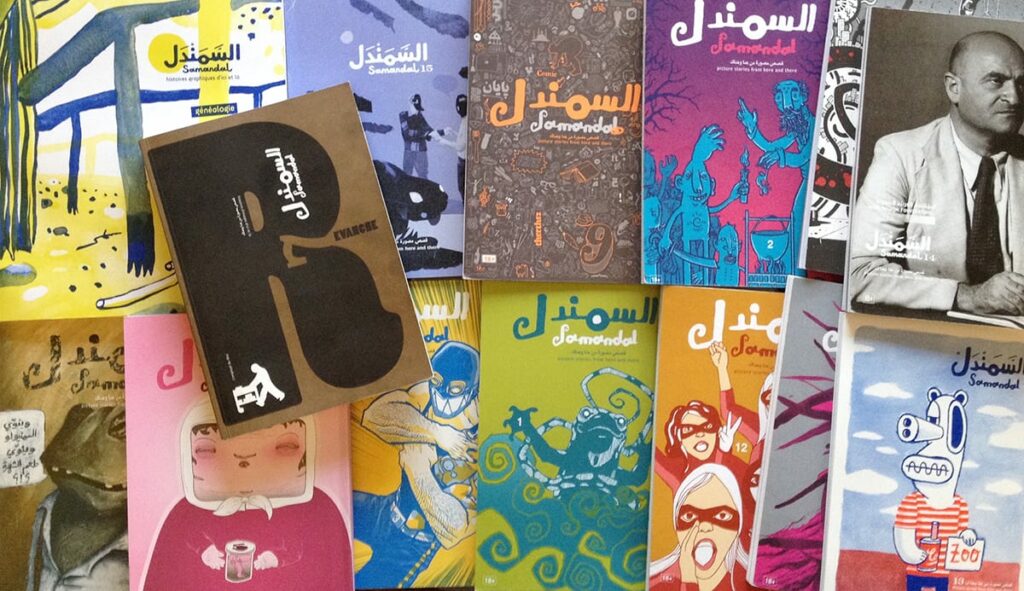

Marginalization and gender are major themes in Joseph’s current illustration and comics work. Joseph is part of the collective Samandal Comics with which he edited two collective books: “Geography” and “3000”, along with a new series of solo books of different authors. Joseph exhibited his work in Brussels, Angoulême, Paris, Lyon, Berlin, London and Beirut.

I met with Joseph to discover a little more on his work :

Joseph Kai, we have a crush on your graphic novel “L’intranquille”. Can you tell our readers what it is about ?

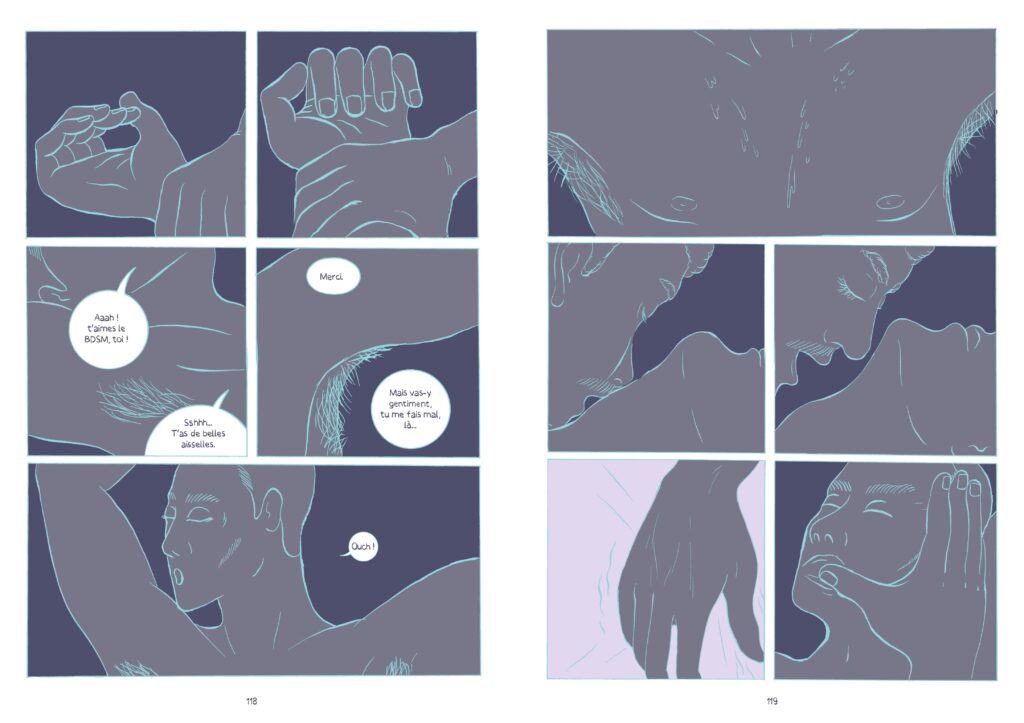

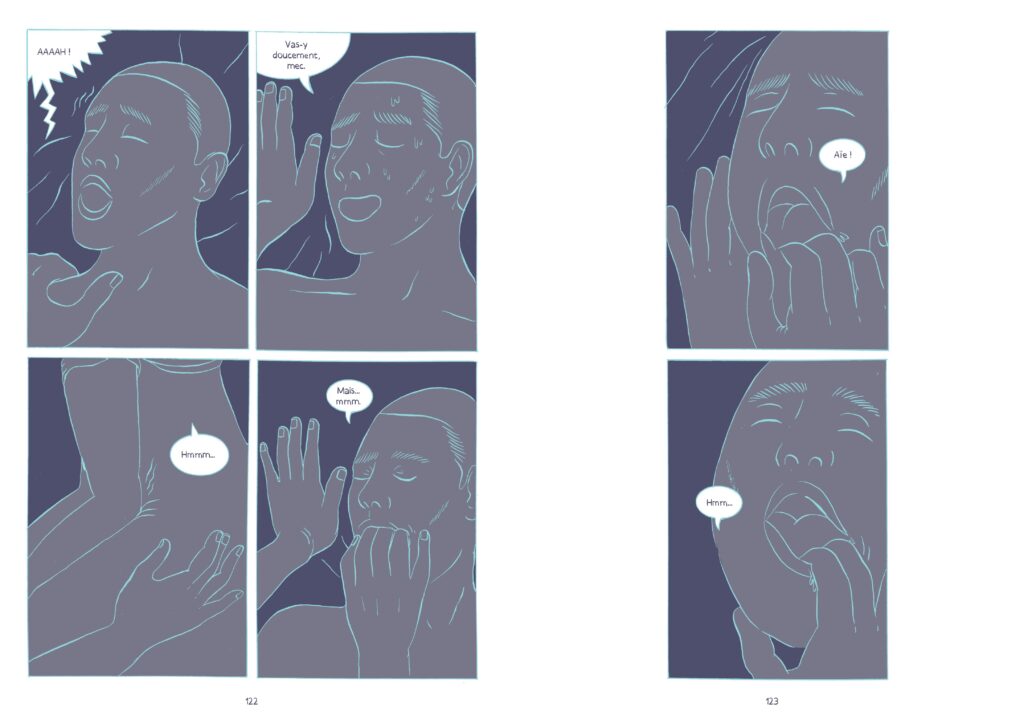

So the story happens in Beirut, 30 years after the end of a long and horrible civil war. Samar is a young graphic novel artist trying to write his first book. The world he lives in triggers a lot of his anxieties on a daily basis: ones that are related to his security as a gay person living in Beirut, his future, and his art. The book is a series of moments: anxious dreams, childhood memories, love stories, and strolls in the underground scenes and sceneries of Beirut. Through the eyes of Samar, we witness the gaze of a whole community living in Beirut, at a moment where the city experiences one of the most radical changes of its contemporary history.

How much of yourself is there in your main character Samar ?

A lot of my character traits are in Samar, but he is not really me. A big part of him and what he experiences in the story are fictional. I need to keep this distance from him, even though I tell his story using the singular first-person. I need the freedom to use my own stories in Beirut and romanticize them, making em more or less specific or likely. Also, many aspects of my own stories are ones that I avoid telling for now. I want to keep my secrets, get inspired, or take whatever I need from them, but then make up new ones.

The questions of censorship around the lebanese queer community is addressed in “L’intranquille” as well as LGBTQIA+ and women rights, gender, sexuality and marginalization. How is it right now to be a queer person in Beirut ?

There’s no clear answer to this question: there are lots of different experiences and voices that can be made invisible if we try to narrow this down to a clear answer such as “yes it’s super cool to be queer in Beirut” or “no it’s so difficult and dangerous to be queer in Beirut”. Both of these answers are incorrect. Also, it’s been 3 years that I don’t live in Beirut anymore and I know that a lot has changed since the beginning of the collapse, so I can’t really pretend to know how it is right now to be a queer person there. I could say that, from 2008 to 2018, for me personally, being queer was possible, and impossible in so many different ways. It was possible to find underground safer spaces (clubs, bars, collectives, groups) where one can be out, it was also possible to feel alienated in these same spaces, it was also possible to be discreetly queer or in the closet without feeling the invasive pressure of coming out, it was even possible to get arrested for practicing sodomy, or kiss in a club and feel safe, etc. This might sound very vague and paradoxical, but what matters to me are individuals, what they feel and experience in all this, and how to give more care.

Can you explain us about your journey from collaborating with Samandal comics collective in Lebanon to having your first novel being published by Casterman here in Belgium ?

I discovered Samandal when I was still a student in Beirut. When I saw their publications, it was very clear to me that this is where comics are happening in my city and that this is where I want to belong. I was lucky later on to get introduced to the group and take part in the editorial team. At a later stage, I got involved considerably in bigger projects aiming at giving a new editorial direction to the collective. This long experience was a sort of rite of passage: being a graphic novel author went from being an ideal ambition to a possible everyday practice, with the help of others, by joining forces and by self-publishing. I learned a lot about editing, layout design, printing techniques, book-making, etc. and moslty, I published many short stories that I consider as preparatory work of what I do now and of L’Intranquille. Samandal was a platform where I could try things, make mistakes and experiment.

You are often in Brussels. Tell us what you like about our city ?

I love the fact that Brussels is a small and very eclectic city. The landscape changes quickly from a neighborhood to the other, and this reminds me a bit of Beirut. In addition to that, I have very solid friendships there: the artist Barrack Rima is part of our group of friends and artists, I’ve learned a lot from her and she hosted me many times in her atelier in Brussels, to take time off, discover the place, draw etc. Also, I’m a close friend and admirer of the team of L’employé du Moi and their publications, Rebecca Prosper and Elisa Huberty and their socio-politically engaged art space “That’s what X said“, my editor Nathalie Van Campenhoudt, and the team of Casterman my publisher.

You are very present in the queer Brussels scene. We saw you at AIWA festival by Lagrange Points and at Thatswhatxsaid gallery. How did you collaborate on those projects ?

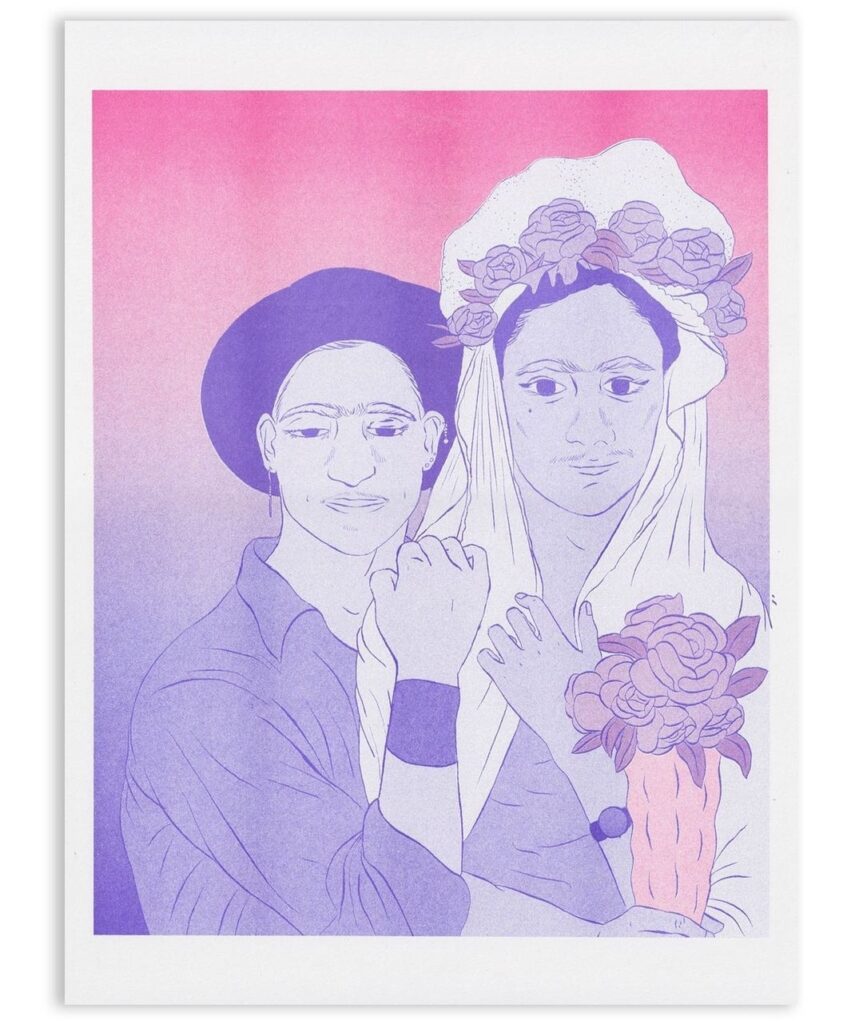

Barrack Rima had initiated the queer festival Aiwa with the team of Lagrange Point, they invited me to take part in it and present my book L’Intranquille in public. It was an important moment for me, I was talking about the book for the first time, and I was lucky to do it in a safe space for LGBTQIA+. On another hand, Elisa and Rebecca from TWXS gallery, contacted me around the same moment to discuss showing my work in their new store/gallery, and I was very excited about it because it seemed very specific and engaged, and I didn’t have any prints available in Brussels back then. I’m happy that now, through their Instagram account I’m also learning a lot more about the struggles and actions taken by minority communities in Brussels, and feel way more aware and involved even though I don’t live there.

What is it about your drawing techniques and the colors you chose to use that sublimates queer characters ?

I enjoy representing my characters with few thin lines and then focusing on specific details that make them different and queer. It could be a morphological or styling detail. Some of them might look awkward or puppet-like, but this doesn’t really bother me, I like that in-between human/robot aspect. Also, I feel that this translates in my choice of coloring as well. I often go for limited and unrealistic color representations for skin, but also for the sky, the ambient light etc. It might be the unconventionality of this, coupled with a rather realistic theme and tone of voice in storytelling, that gives the queer aspect to my characters or work in general.

Pictures credits : Sama Beydoun, Joanna Kai, Samandal Comics, Quintal Atelier,

You may also like

-

Interview with JJ, Eurovision 2025 Winner: “Live Each Day with Pride, Because We Are Unstoppable”

With his “pop opera”—as he defines his music—JJ brought victory to Austria at the recent

-

Midsummer Mozartiade: Celebrating Mozart and the Labyrinth of Love in Brussels

From June 17 to 22, the Midsummer Mozartiade festival returns to the heart of Brussels

-

Edy’s VERTIGO : Finding Truth Between Borders and Beats

” I was afraid to surrender,” says Edy Dinca, the Brussels-based queer artist behind the

-

Valenciaga – Born form love, dressed in power

Brussels is well acquainted with queer creativity, but sometimes a voice emerges that leaves a

-

DAY-8-“Safety, Dignity, Belonging” Andrea’s mission at Wowen Now

In Brussels, Andrea from Women Now is on the front lines supporting LGBTQIA+ migrants and