20 years ago, Belgium was the second country in Europe – and in the world – to make access to marriage independent from the legal sex of the partners. The exact formulation remains convoluted. “Two persons of different sex or same sex can contract marriage”, says the law. Well, better written, two persons can contract marriage. And that, regardless of the legal sex they were attributed at birth.

Over the last two decades, this innovation launched by the Netherlands in 2001 would be replicated in 18 other countries in the continent. Yet, the battle for marriage equality is far from being over in Europe. But there is hope that equality is within reach.

A steady progress in the West

After the Netherlands and Belgium, Spain was the third European country to adopt marriage equality in 2005. These three countries were soon joined by Nordic countries – Norway and Sweden in 2009, Iceland in 2010, Denmark in 2012 – and by Portugal (2010). After a long series of demonstration and counter demonstrations, France – which was an early adopter of same-sex civil unions in 1999 – adopted its reform of marriage using Belgium’s formulation in 2013.

In 2015, Ireland was the first country to adopt marriage equality following a referendum to amend its constitution to grant marriage to two people regardless of their legal sex. The referendum was won with 62% of the vote, a revolution in a country perceived so far as conservative on societal issues. Progress continued to cover all Western Europe with Luxembourg (2015), Finland, Malta, and Germany (2017), Austria (2019), United Kingdom (2020), Switzerland (2022), and Andorra (2023).

Some countries, however, are still missing on that list. Greece and Italy, which adopted same-sex civil unions in 2015 and 2016, are the only two old members of the EU not recognizing marriage equality. If proposals have been tabled by the opposition in Greece, it is unlikely that the situation will evolve in Italy under the government of Giorgia Meloni, a key international figure of the so-called ‘anti-gender’ movements.

A rising opposition in the East

While the situation was progressing in the West, opposition to equality fueled constitutional reforms in the East. Whereas same-sex partnerships had been approved in Hungary in 2009 under a progressive government, Viktor Orban’s crusade against LGBTIQ+ people started in 2012 with the adoption of a constitutional reform that would describe marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Croatia adopted similar modifications following a referendum initiated by Catholic groups held in 2013, although recognizing same-sex partnerships in 2014. Slovakia followed in 2014.

With Bulgaria, Latvia and Lithuania, there are now six EU countries where the road to marriage equality will require a modification of the constitution. These countries are legally bound by a 2018 ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union – the Coman case – to provide residency rights to foreign same-sex spouses of EU citizens. Nevertheless, Romania – who refused residency to the spouse of M. Coman – has still not implemented the ruling. And the European Commission has still not taken any step to force Romania to do so.

The fall of the “pink curtain”

It seemed for some time that marriage equality was bound to respect an East-West divide in Europe. And yet, what has been labelled as a ‘pink curtain’, in reference to the former ‘iron curtain’, started to fall apart a few months ago. Following a complaint by two same-sex couples, the Constitutional Court of Slovenia stated in July 2022 that forbidding access to marriage to same-sex couples was unconstitutional. This ruling immediately opened marriage to same-sex partners, the law confirming the ruling being adopted in October 2022.

Slovenia then became the first post-soviet country to adopt marriage equality. The first one to open a hole in the ‘pink curtain’. Looking into the future, others are bound to follow. The polls and recent elections in Czech Republic and Estonia bring hope for marriage equality to arrive soon in these countries. A possible victory of progressist forces in Poland in Autumn 2023 could also bring some radical change in a country often portrayed as very conservative on this topic.

Further East, Constitutional modifications were adopted recently in Armenia (2015), Georgia (2018) and Russia (2020) to ban same-sex marriage. Putin has been justifying its war in Ukraine with the argument to protect Ukrainians from the ‘decadence’ of the West – meaning in his words the rights of LGBTIQ+ people. Yet, if the current martial law in Ukraine prevents a needed constitutional reform on marriage equality, a bill has been introduced recently to recognize same-sex partnerships in Ukraine.

As the ‘pink curtain’ starts crumbling, let’s all commit to join our efforts so that in 20 years from now marriage equality will be a reality for all Europeans.

You may also like

-

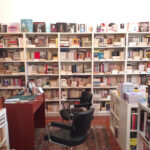

Vigna in Nice: Where Queer Books Breathe and Memories Live On

Right in the heart of Nice, there’s a bookshop where stories don’t just sit quietly

-

The BGS Winter Retreat: 12th Edition in Serre Chevalier

Every winter, a vibrant tapestry of familiar and new faces gathers from the BGS LGBTQIA+

-

“The Bundestag Is Not a Circus Tent”: Chancellor Merz Faces Backlash Over Rainbow Flag Refusal

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz is at the center of a political storm after backing the

-

Épicentre: Inclusive Health and Well-Being for All in Brussels

Located in the heart of Saint-Gilles, Brussels, Épicentre is a multidisciplinary center dedicated to care,

-

Daryacu: A Safe Haven in Brussels for the Marginalized and Vulnerable

In the heart of Saint-Josse, Brussels, a unique project is quietly making a big difference